Boyd Chubbs: Gifts Never Lost or Traded

Christina Parker Gallery is pleased to announce Gifts Never Lost or Traded, an online exhibition of new work by Boyd Chubbs.

“Gifts Never Lost or Traded”: Drawings by Boyd Chubbs

Peter Sanger

Enigmatic, seemingly anachronistic, anomalous images frequently occur in Chubbs’ drawings. About three-quarters of the works in his new exhibition contain such images. They both surpass and sustain. They surpass by implying their origin is otherwhere than in the artist’s skill and knowledge or in the viewer’s experience of ordinary possibilities. The images sustain by evidencing that attention, patience, justice, love and beauty exist and are active. For some of us, such images move to tears. For others, they connote nothing or are self-deluding obscurities. Chubbs has always chosen the more difficult way of the two, the way of affirming the images.

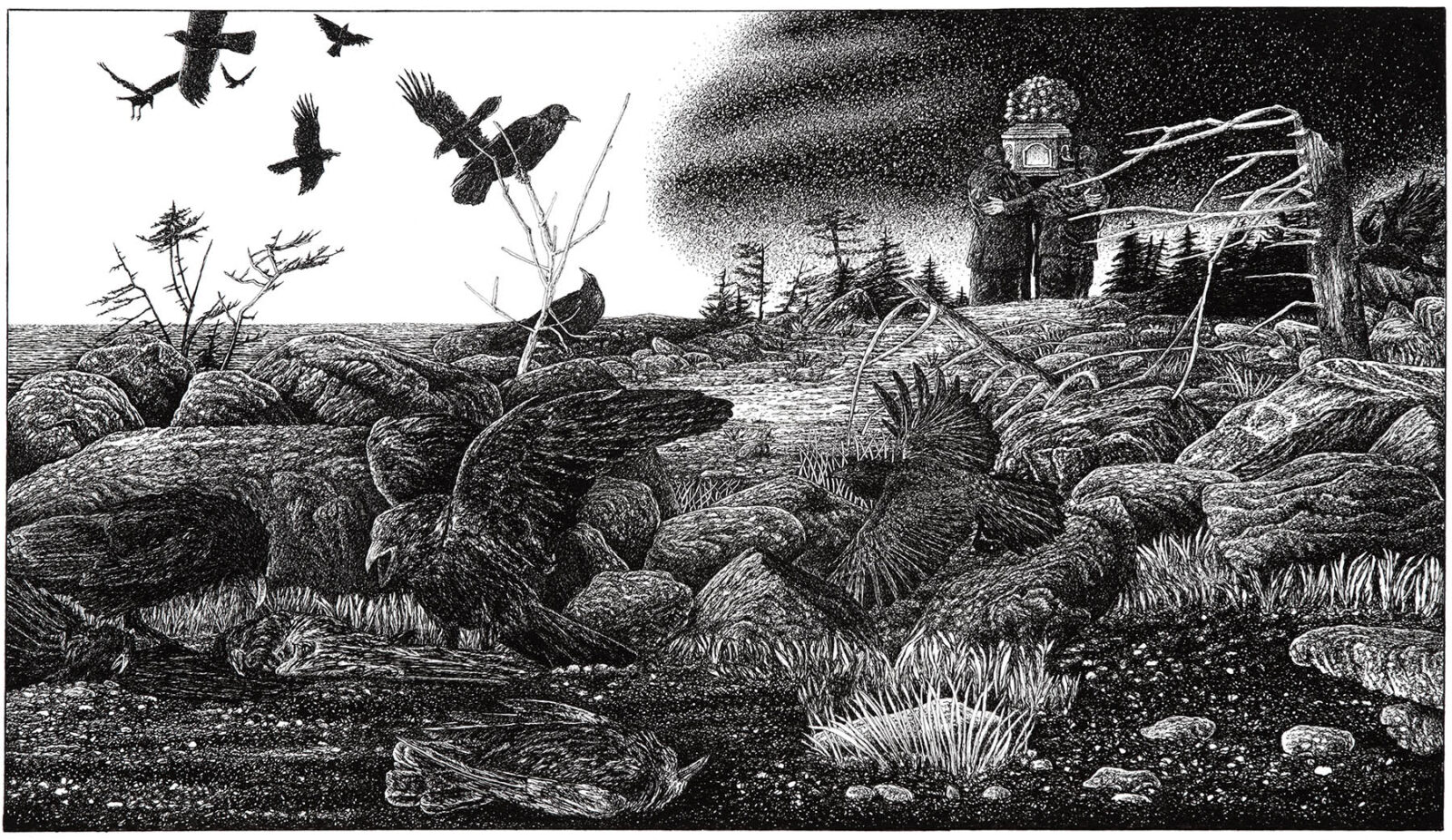

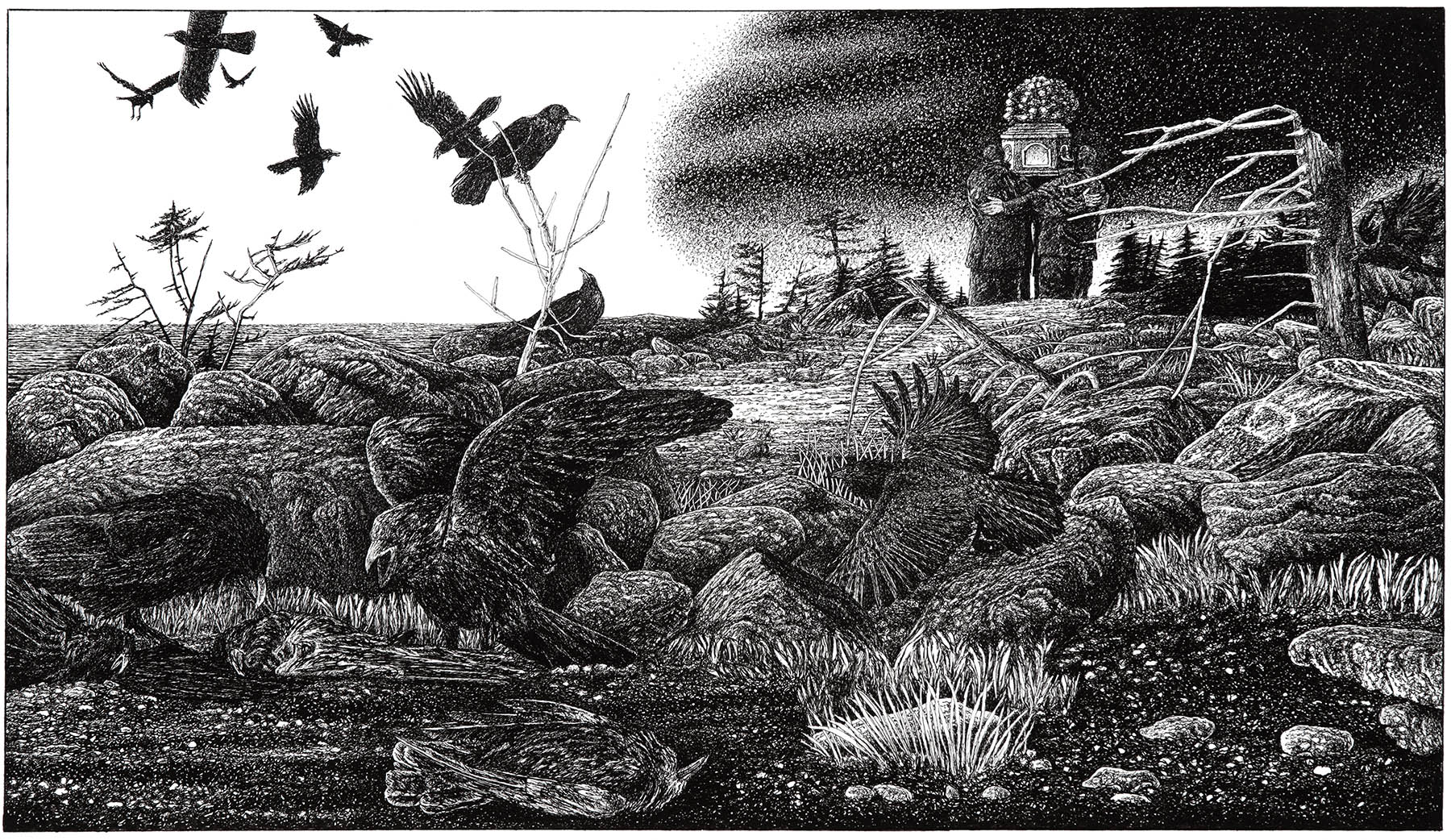

Two Funerals, 2021

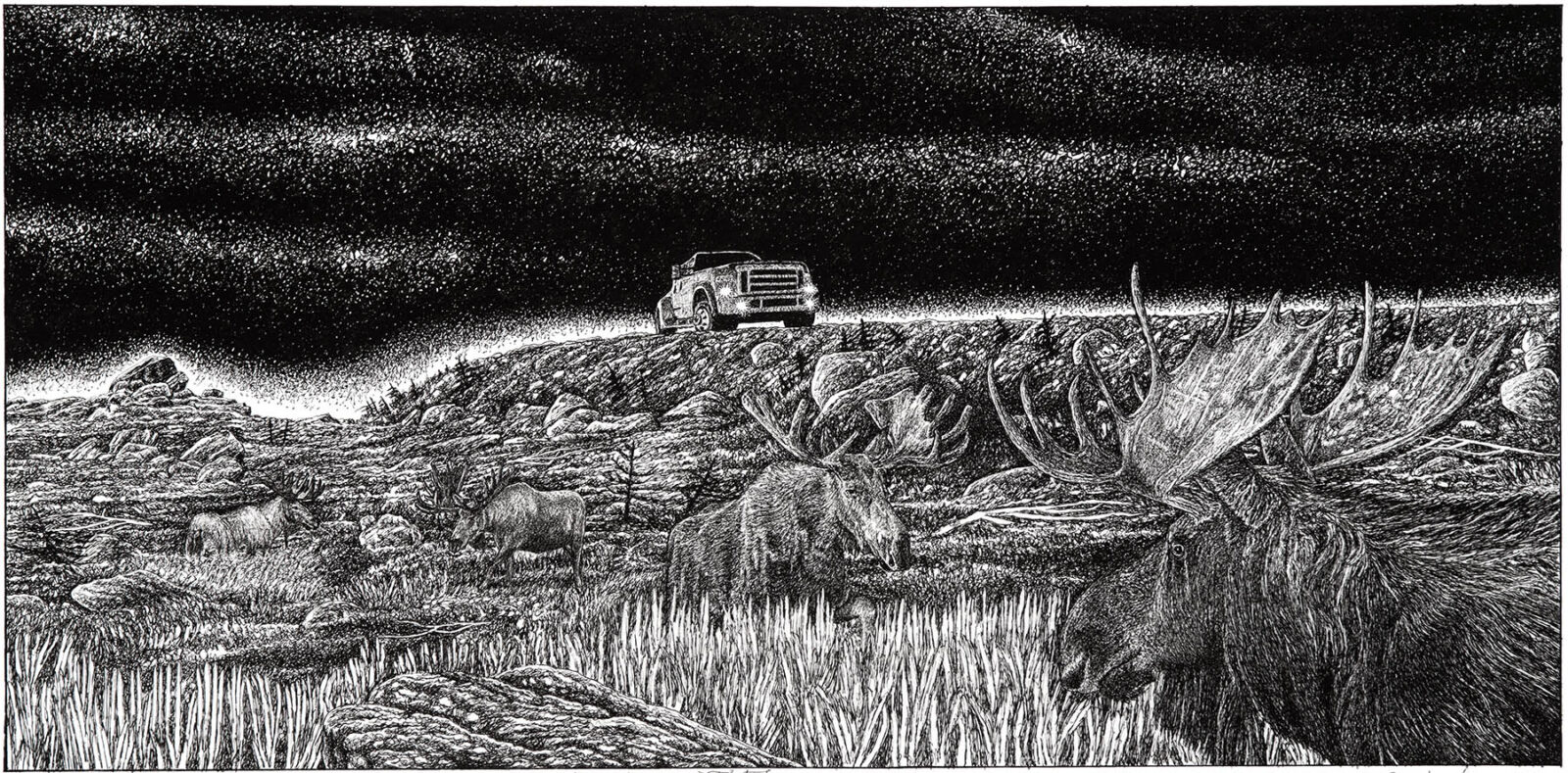

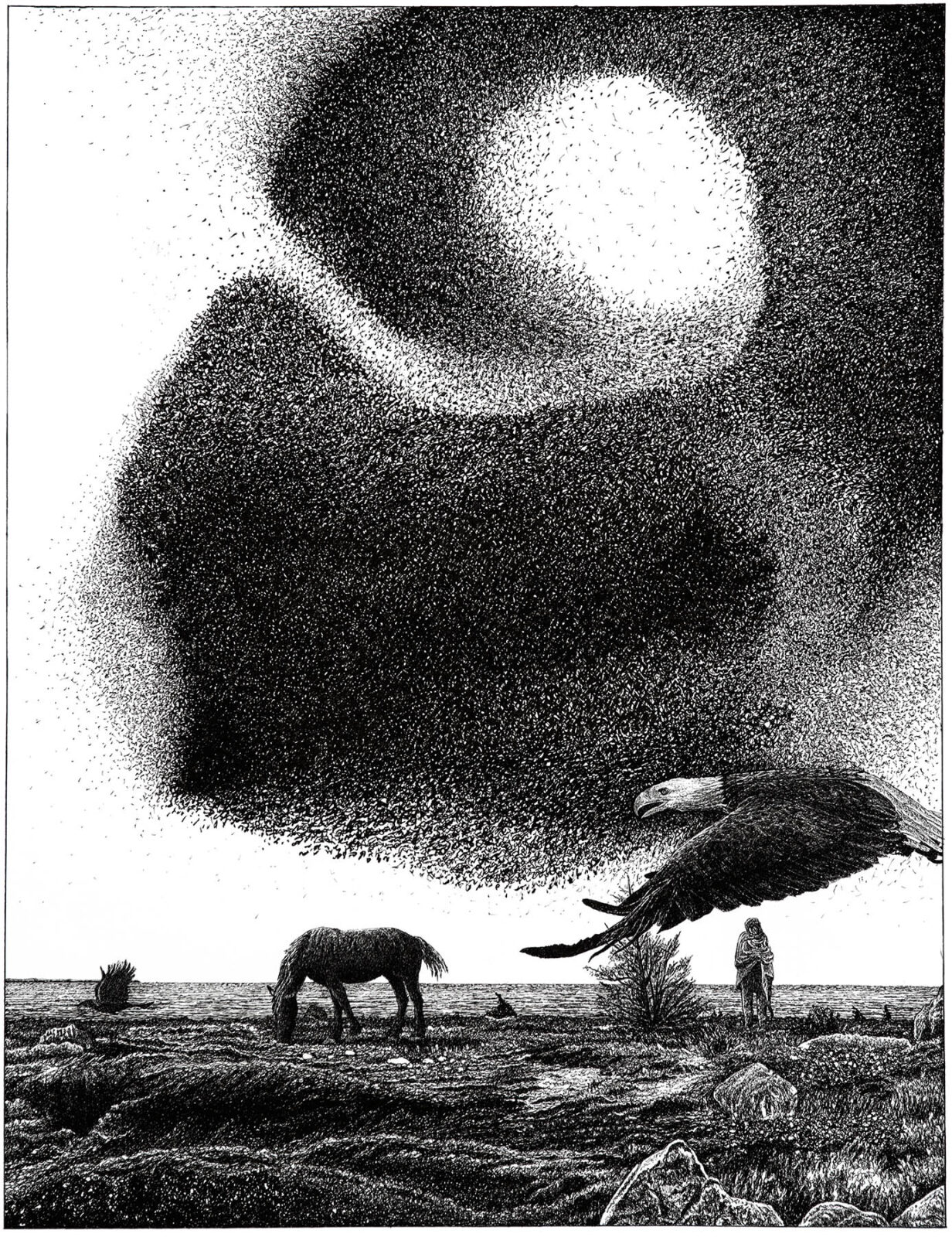

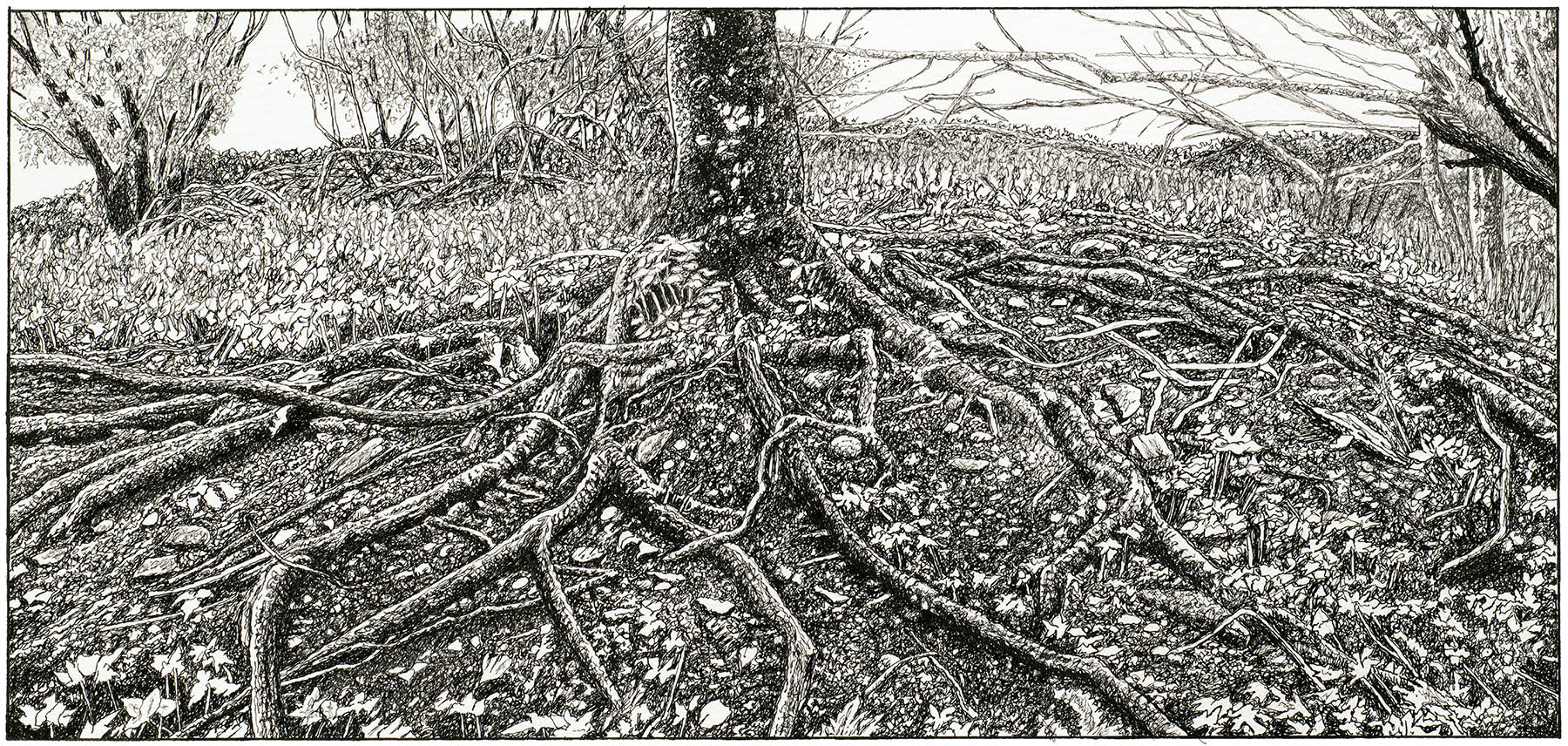

In his work there are sudden incursions of dream into wakened circumstance; unexplained juxtapositions of birds, animals, humans charged with both violence and benevolence; co-inherencies of birds, whales, horses, rock, trees, ocean, icebergs, sky, moonlight, sunlight, starlight. They present themselves in drawings of meticulous, patient, realistic detail, with a consciously Blakean rigour of outline. Because they are minute particulars, Chubbs counts the feathers in an eagle’s wing and accounts for each singular rock on the barrens, images given, images entrusted, images lent, images raised and released by the artist into autonomous resistance, autonomous existence.

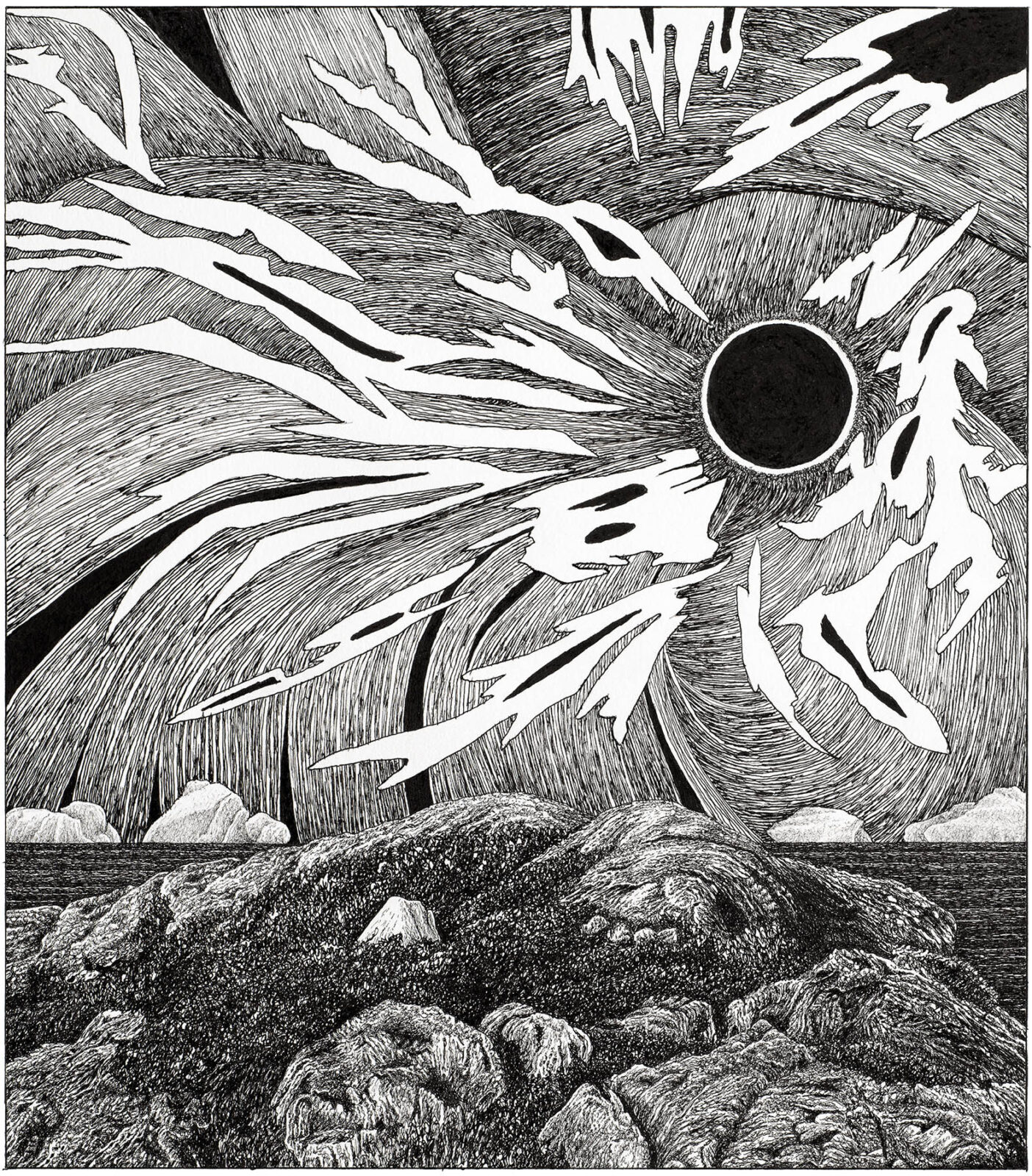

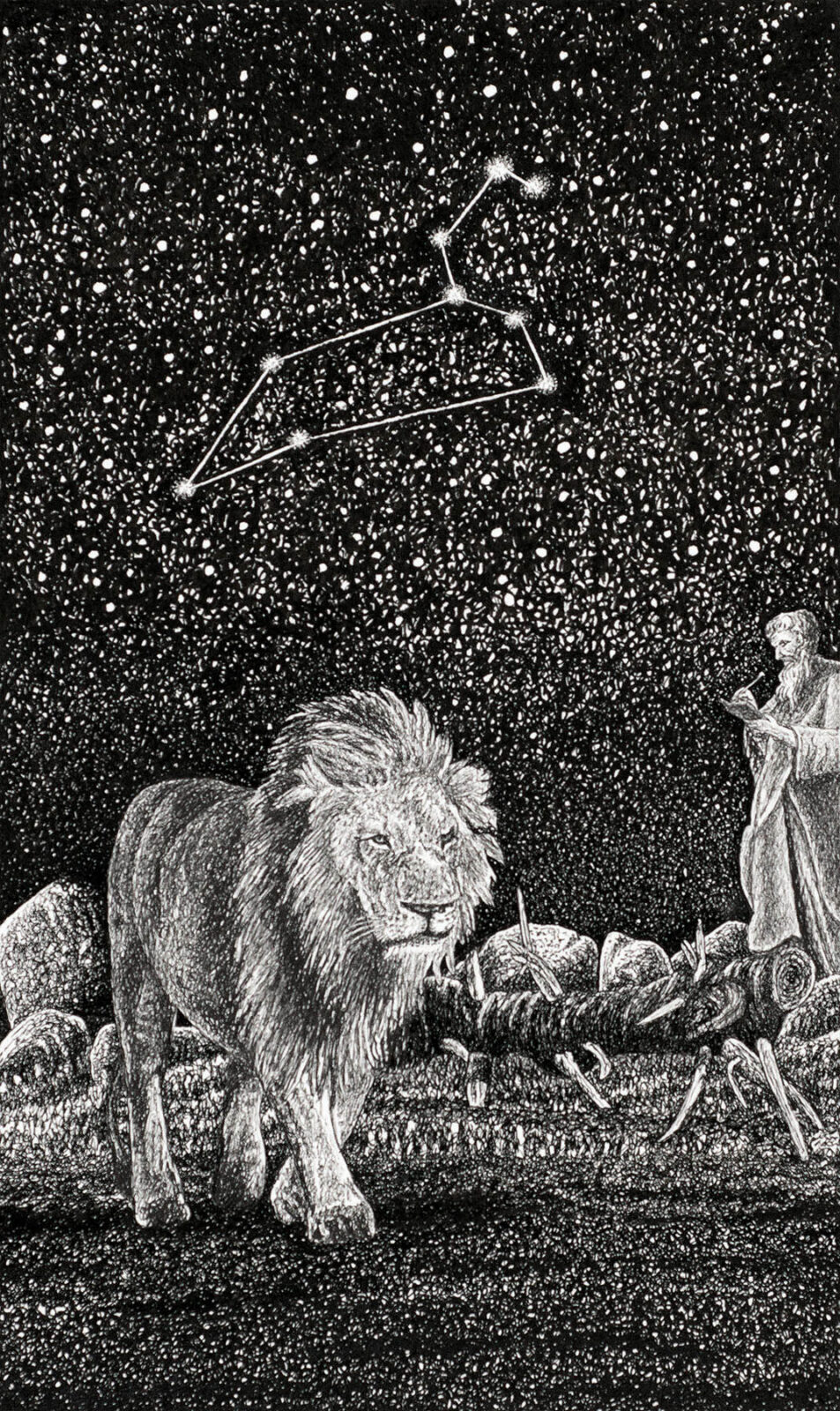

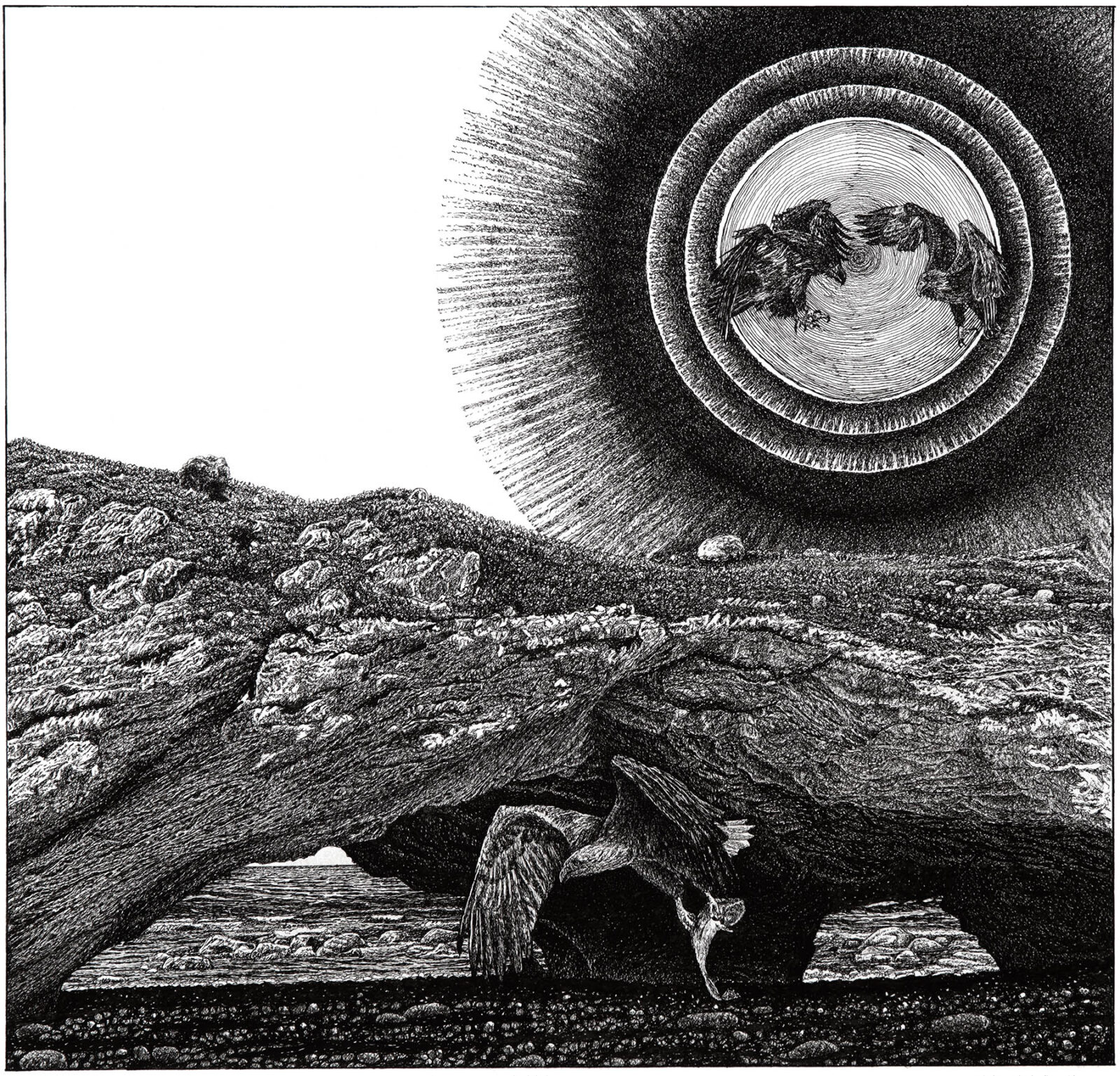

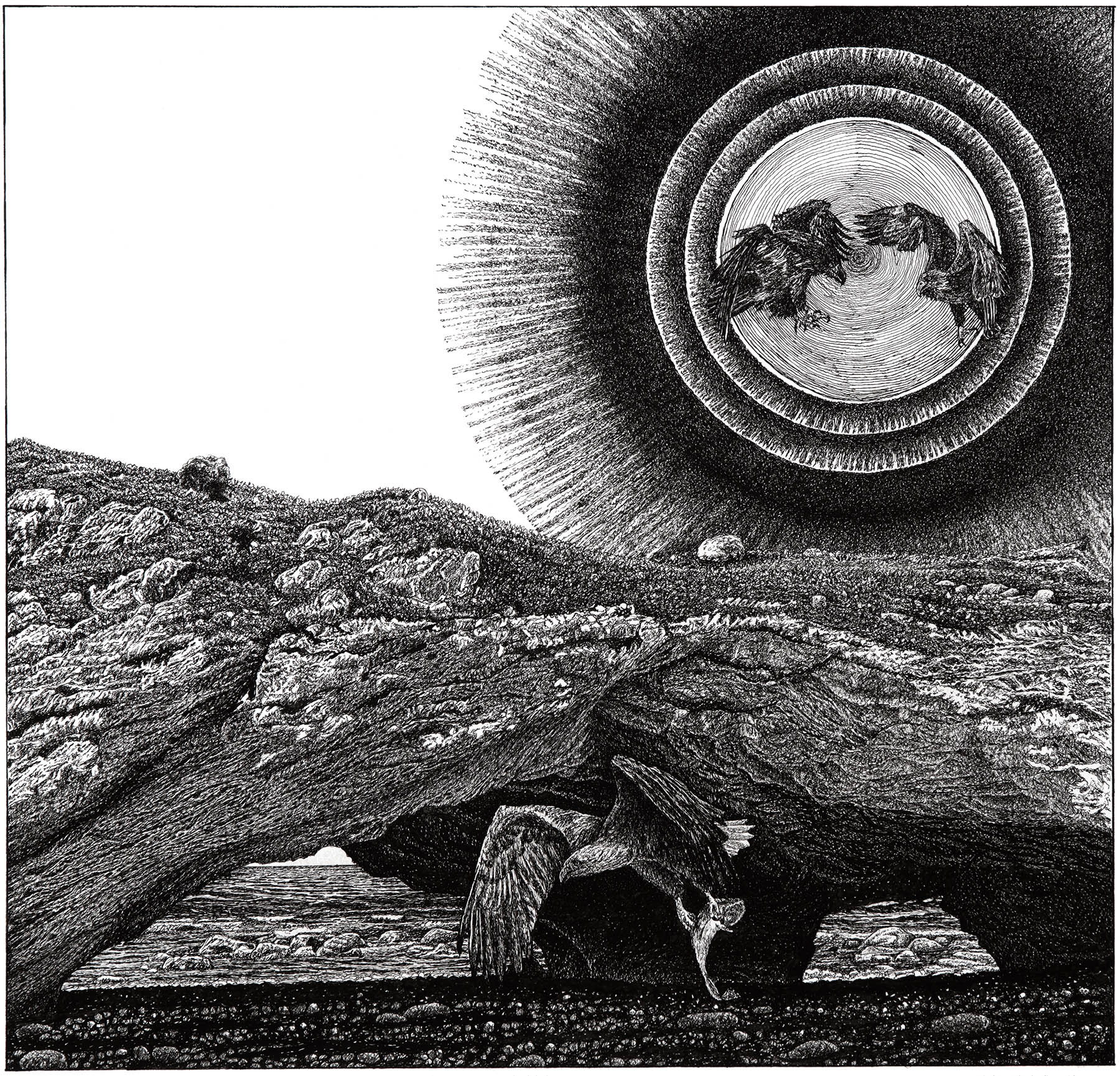

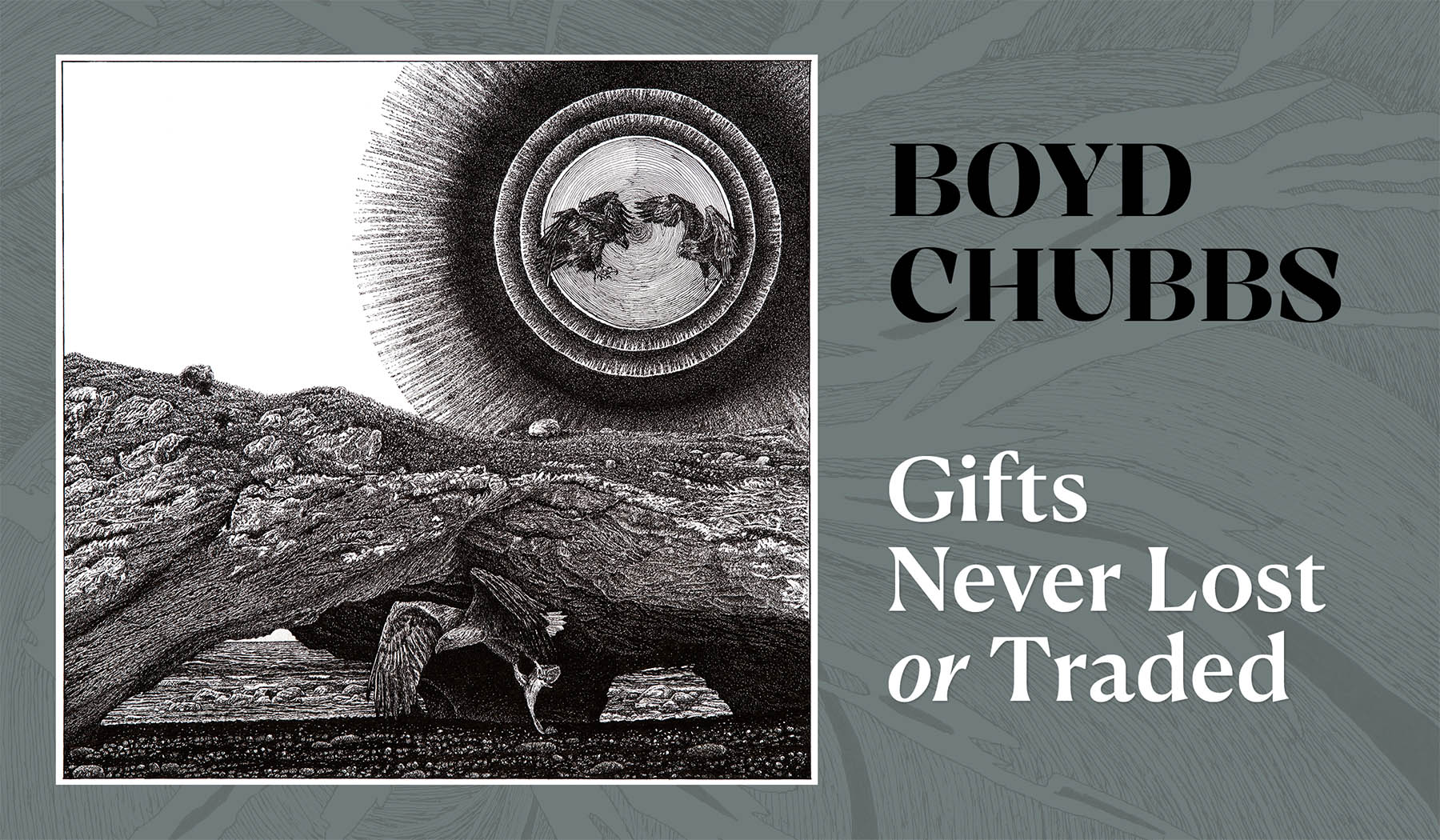

Chubbs’ images resist the simplification of poor abstract thinking. No stabilized meaning, for example, can be assigned to the crows, ravens, and eagles that appear frequently in his recent work. They may be associated with death in the pictures, but they do not represent death. Closer to the truth, they represent life in death and death in life, and that assertion resolves into paradoxical accuracy which is very characteristic of Chubbs’ latest work. There is an example in a dramatic drawing set at the Arches, a famous hollowed out rock formation on the Great Northern Peninsula. The picture is dominated by a black sun within the circle of which two eagles are fighting. Their fight is stylized into a heraldic design. In the foreground a third eagle, more fluidly represented, flies away with a fish in its talons. Written beneath, in the beautiful calligraphy Chubbs uses, is its title: “Daily Bread and Strife, by the Arches”. The “and” in the title does not signal addition. It signals co-equivalence. The “Daily Bread” comes from the Lord’s Prayer. The co-equivalent “Strife” is usually used in English translations of the surviving fragments of the philosophical speculation of the Greek thinker Heraclitus who believed the cosmos is maintained by a balance of force and counter-force as is, to paraphrase one of his examples, the bow by its bow string and the lyre by its tension strings, in a word, by strife. “Daily Bread and Strife…” is one of the key works in the new exhibition, suggesting a way of resolving what otherwise appear to be incompatible antinomies. They are. in a sense, a fugal counterpoint. I have asked Chubbs about the picture’s origin. He told me that he saw everything in the picture when he was eighteen and had left his home travelling with a neighbour in the neighbour’s pickup truck to St. John’s for the first time. The neighbour pulled the truck to the side of the road where a foot path led to the sea and the Arches. Chubbs ran down the path and made what he saw in 2023, some fifty years later.

Daily Bread and Strife, by the ‘Arches’, 2023

On a short breathed human scale fifty years is the equivalent of geological time. Part of the Arches that Chubbs saw has since collapsed into the sea. Chubbs’ drawing meanwhile takes place in the no time of visionary myth time.

I think of another story he once told me. His father, when his sons were out fishing with him, would gently respond to their boasting about the size of their catch and their own skill with the comment that all kinds of other powers had to consent before the fish could be caught. In 1973, at the age of eighteen, Chubbs was both leaving and coming home. He was leaving his childhood and entering his art.

He was born in the Grenfell Mission Hospital in Forteau on the Labrador coast in 1955. His parents lived in L’Anse Au Clair slightly south of Forteau and also on the coast. To reach Forteau back then, Chubbs’ mother had to be taken by the family’s boat, and because of delays and the weather Chubbs was almost born on the hospital steps.

Chubbs’ father, Gordon Victor, was an inshore fisherman using trawl and jig from a small engine wooden boat to catch cod which he salted and dried. He had what Chubbs has described to me “a fine writing hand” and became, without seeking to be, the community communicator with the outside world. He was also a gifted harmonica player. Chubbs’ mother, Una (neé Crib) was born in Forteau. Chubbs describes his parents as “quiet speakers”, hard workers, generous in their charity. For many years Una was organist at the local Anglican Church, St. Andrew’s. There were six boys and six girls in the family. One of the brothers, Eric, “drew and drew” according to Chubbs and also gave Chubbs his first guitar. Chubbs also drew constantly from a young age. Like the rest of the family, he went to St. Andrew’s, and he was impressed by the high style of the hymns, organ music and sermons.

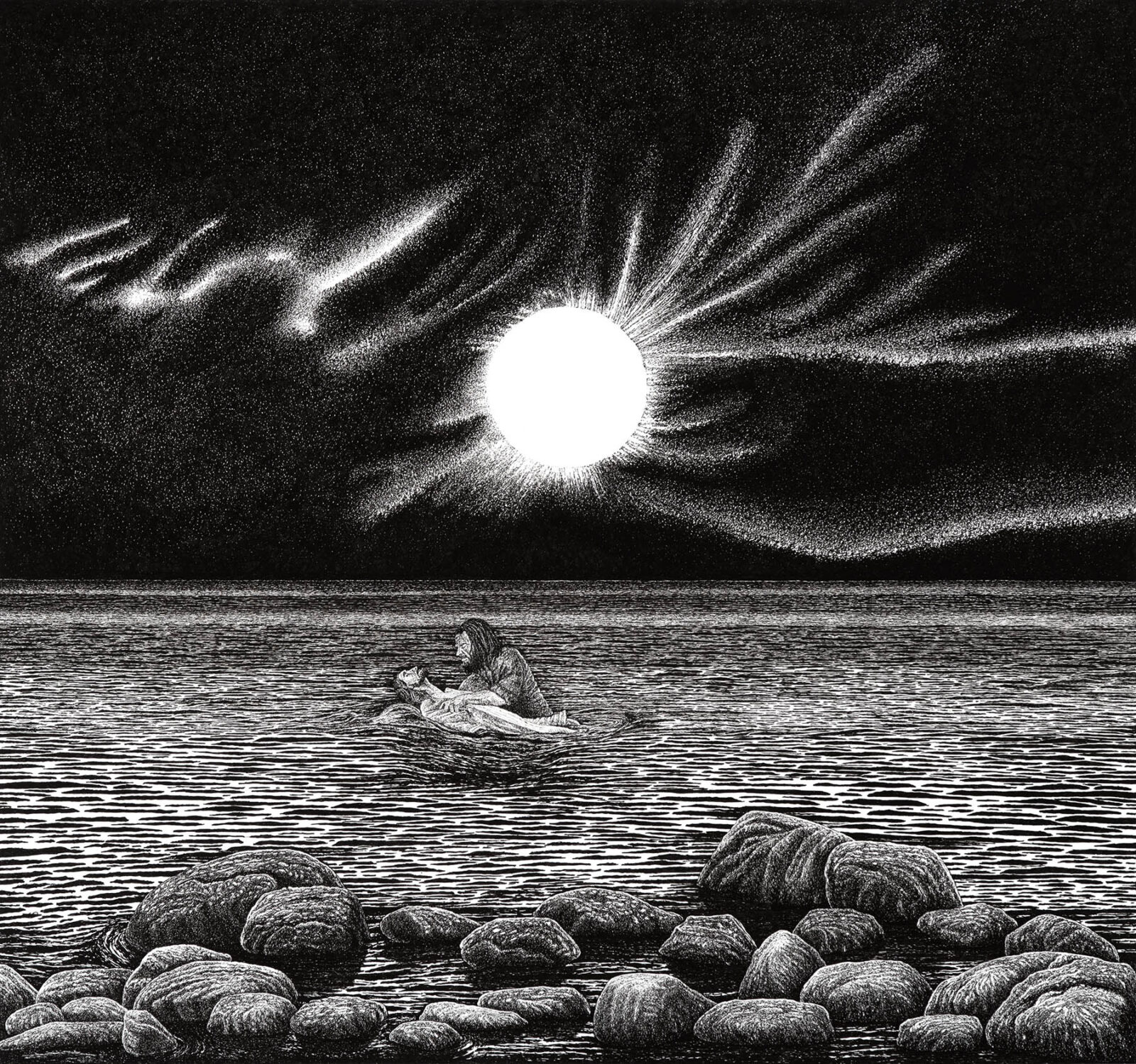

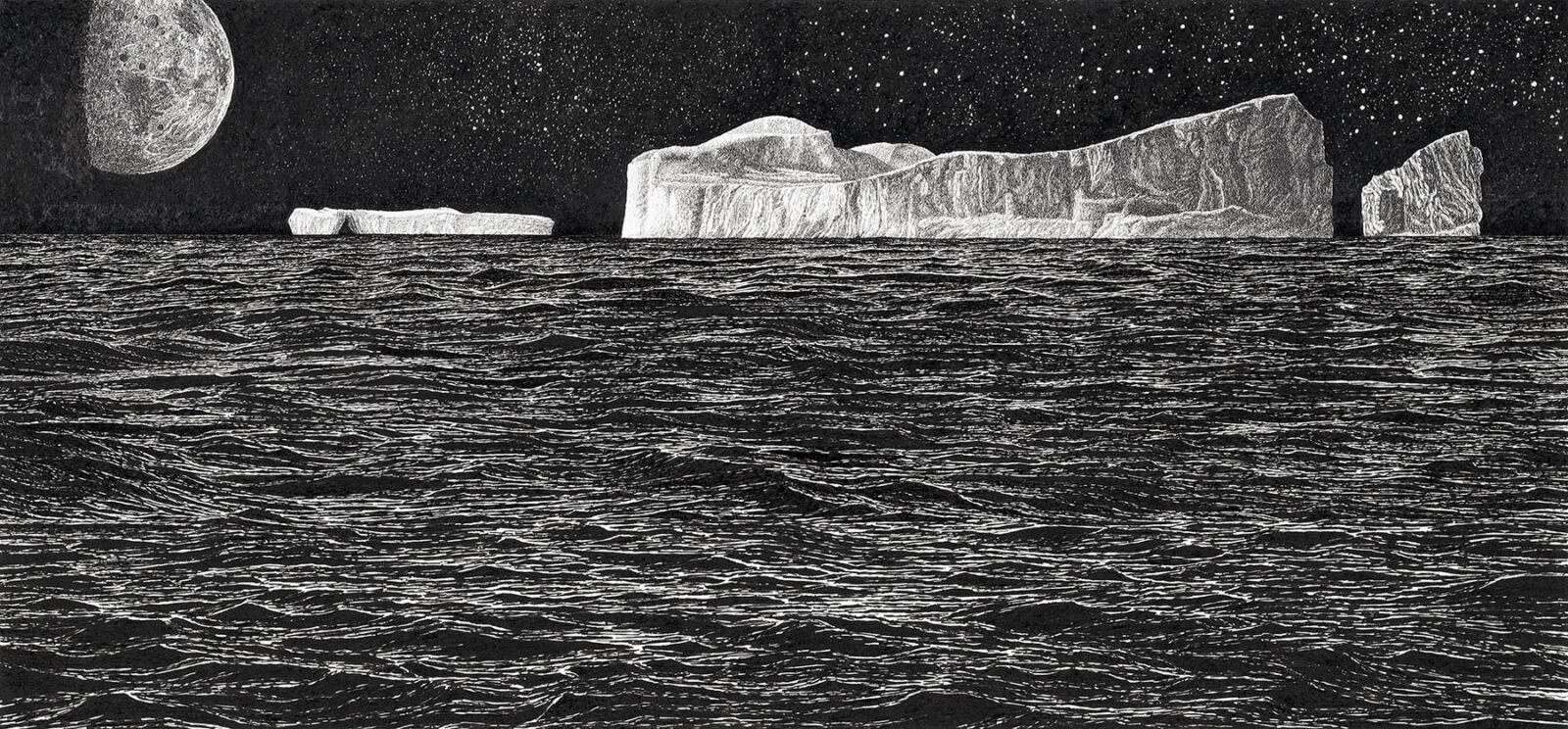

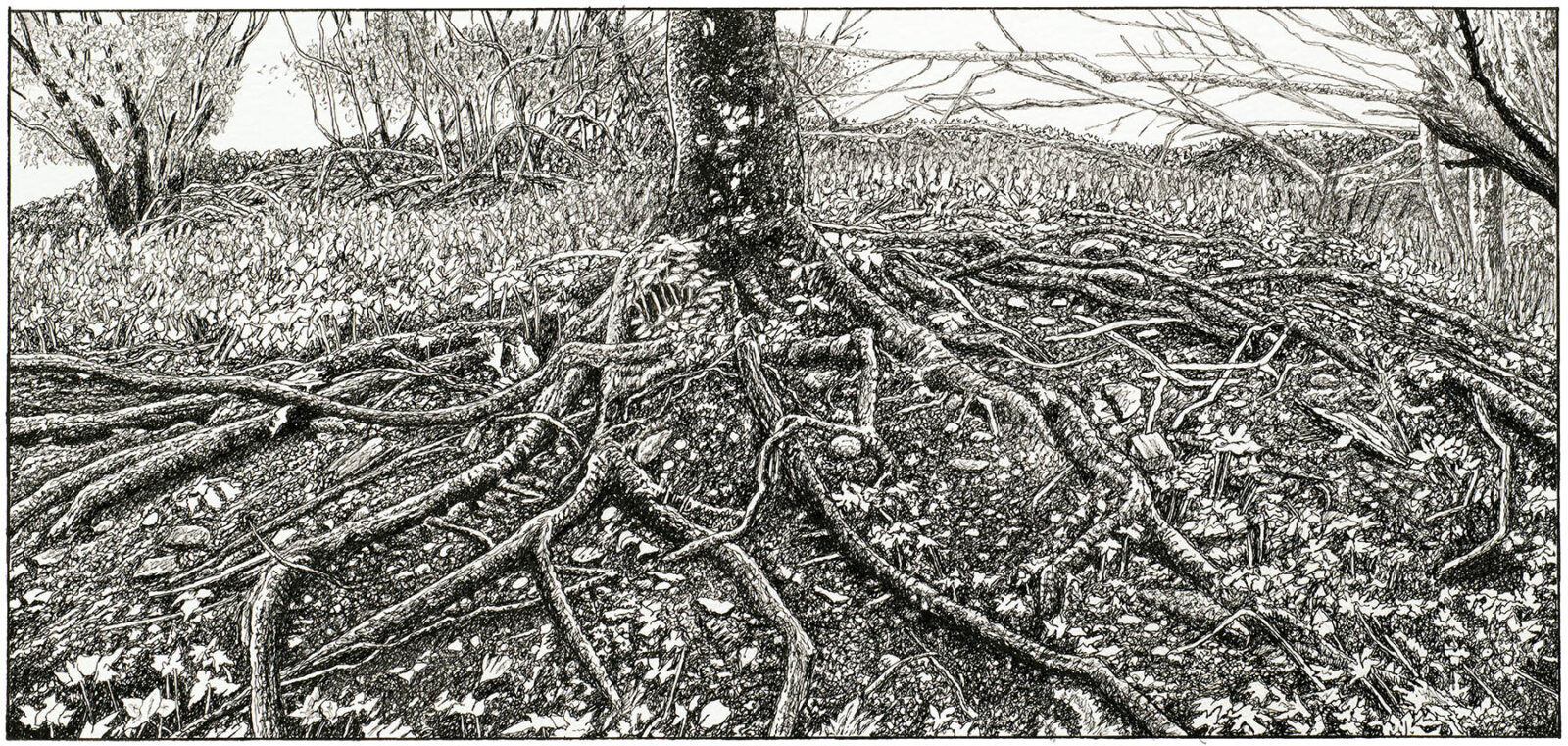

Meditation Upon ‘The Source’, 2024

Chubbs attended high school in Forteau, receiving no particular encouragement in school for his interest and ability in art, music and poetry. He was graduated in 1973 and enrolled in the Commercial Art course at the College of Trades and Technology in St. John’s. He did not complete the course. Between 1976 -1980 he was a full time student at Memorial University enrolled in courses in English, psychology and sociology. He told me he “shunned” graduation.

For many years he has practiced art, music and poetry with great patience and independence. He has supported himself by teaching guitar playing, by working as a solo itinerant musician and singer-songwriter and by virtuoso calligraphy (ornamental inscriptions, citations, memorial addresses, invitations, for example).

If this summary of Chubbs’ life seems too abrupt it is because his life should be told in terms of his art, a procedure which is not really biographical. The immediate subject here is the exhibition at hand. The main concern of the rest of these notes is Chubbs’ recovery of sanctuary, to use a word from the title of one of his drawings. Sanctuary was first discovered by Chubbs in childhood and youth. Chubbs wrote to me once, “my earliest and lasting influences are the sea-barrens, sea rocks, hills and cliffs of my home L’Anse Au Clair”.

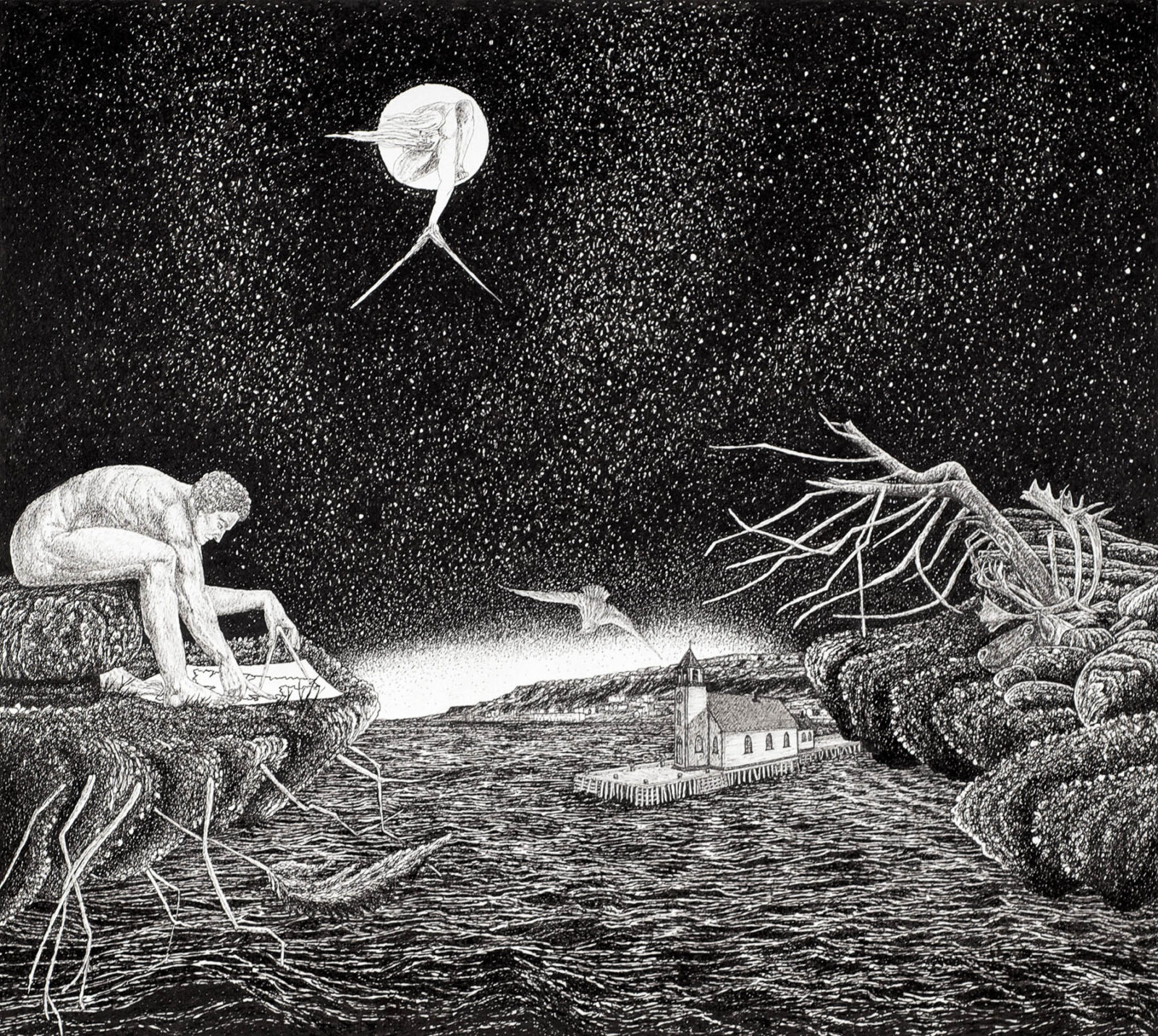

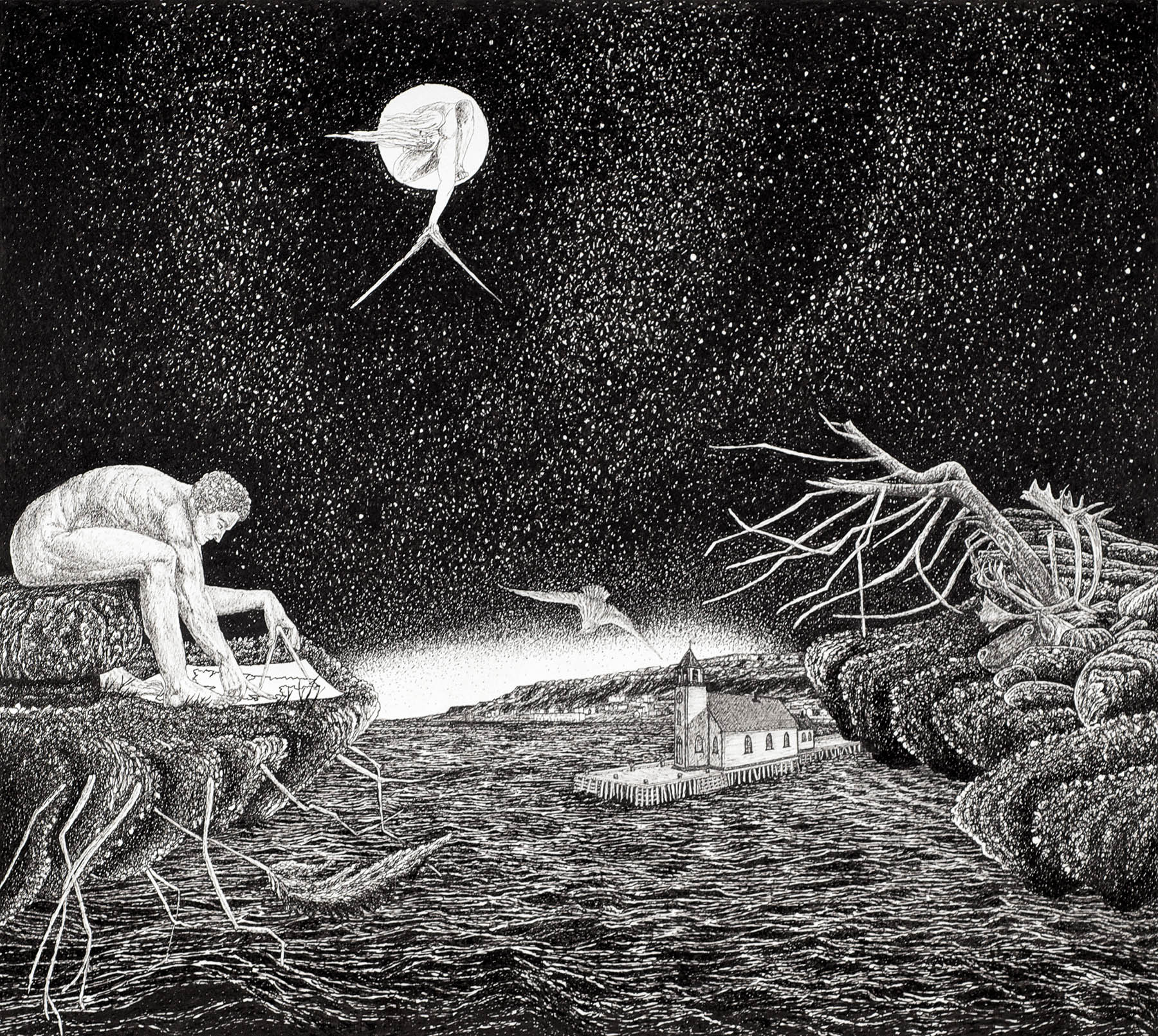

‘Newton’ Receives the News from the Omnipotent…, 2024

There is in fact a visionary panorama of L’Anse Au Clair in the new exhibition. It is dominated by Chubbs’ copies of two of William Blake’s best-known figures. The upper one, kneeling with open compasses as if to take the measure of the outport and its wharf on which stands St. Andrew’s is The Ancient of Days copied from the frontispiece of Europe: A Prophecy (1794). Below him, sitting on a rock, is Chubbs’ copy of Blake’s depiction of Newton (1795), the arch materialist in Blake’s mind. The triangle in Blake’s Newton print which Newton measures with a compass has been changed by Chubbs into a map of Labrador. Just below the centre of the picture is a flying gull, a ghostly messenger of sorts, an Atlantic equivalent of the dove of the Holy Spirit. All three, Ancient of Days, Newton and gull as Chubbs’ title caption tells us are passing on the message that fishermen from L’Anse Au Clair have just drowned. All three are terrible in their beauty, necessary in their strife and are part of the community of bread harboured by a church built literally on the sea.

Seldom is Chubbs so explicit about iconographic sources in his pictures, although in private conversation he never hesitates to talk about Blake with praise, pleasure and gratitude. He wrote to me: “…the Line kept speaking in the most assuring way … the “line” has remained to gather in my narratives”. Chubbs’ reference is to polemical passages in Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue such as “the more distinct, sharp and wirey the bounding line, the more perfect the work of art…leave out this line, and you leave out life itself…”.

The panoramic Blakean drawing of L’Anse Au Clair is an epic version of one of Chubbs’ constant themes, the mutual intricacies of nature, art, belief and human mortality. The length of the title Chubbs uses to designate this epic reenacts the tension it endured in the making: “‘Newton’ receives the News from the Omnipotent, and Grieving measure[s] Grief’s victory for the sea to return the Drowned”.

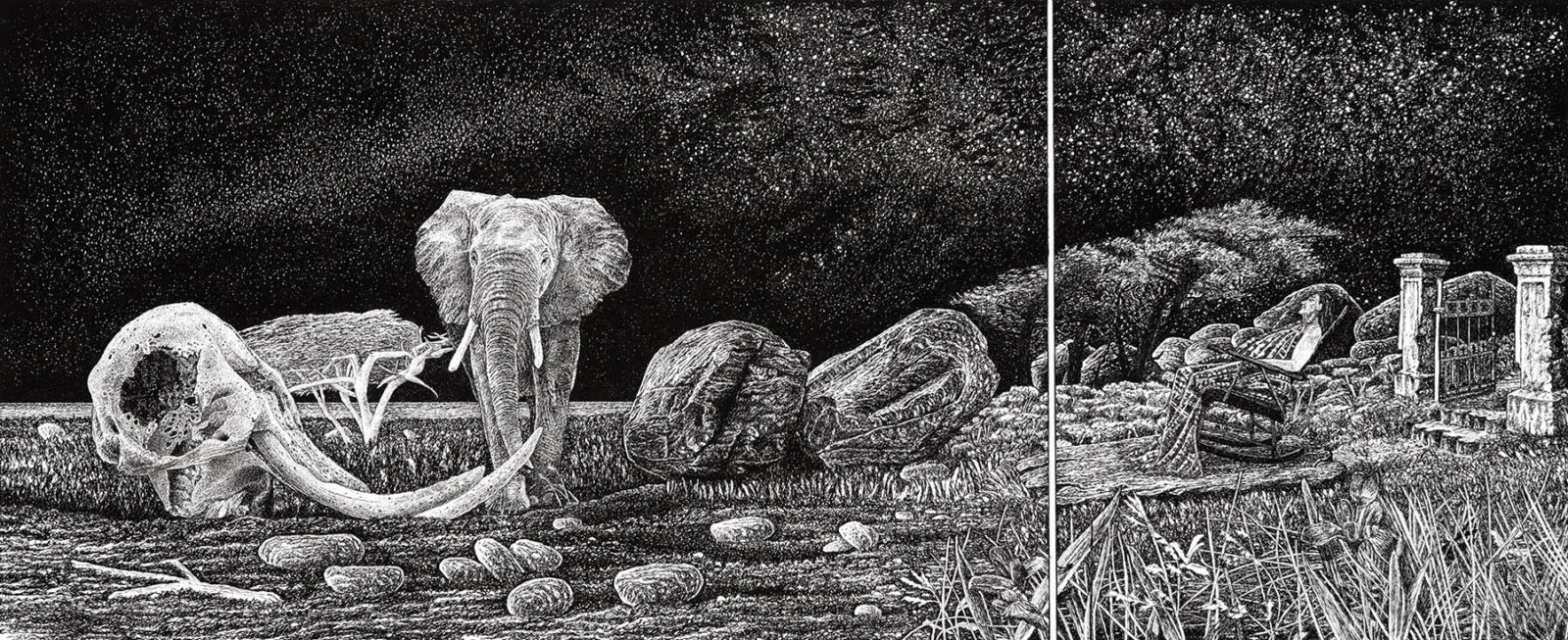

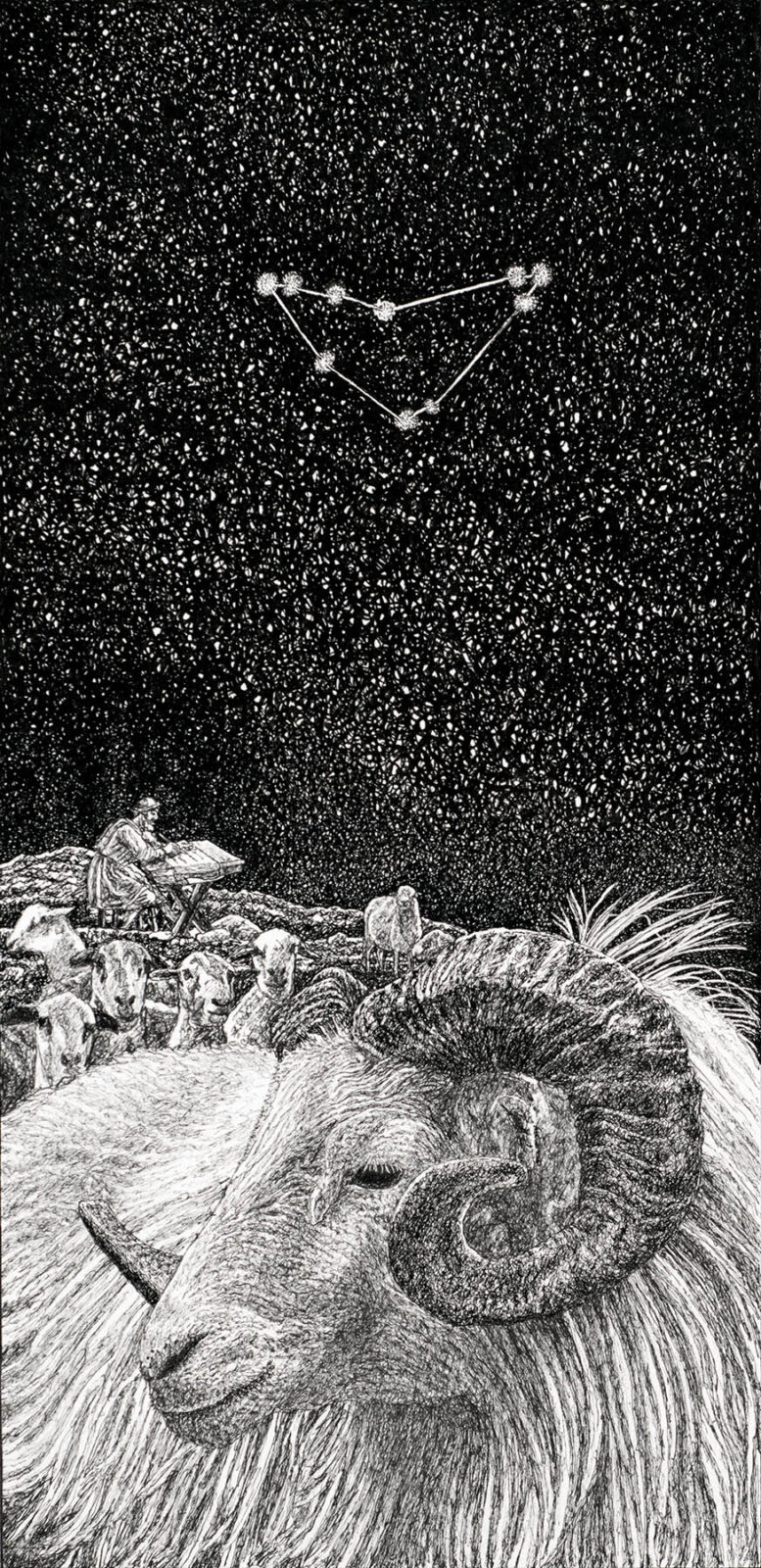

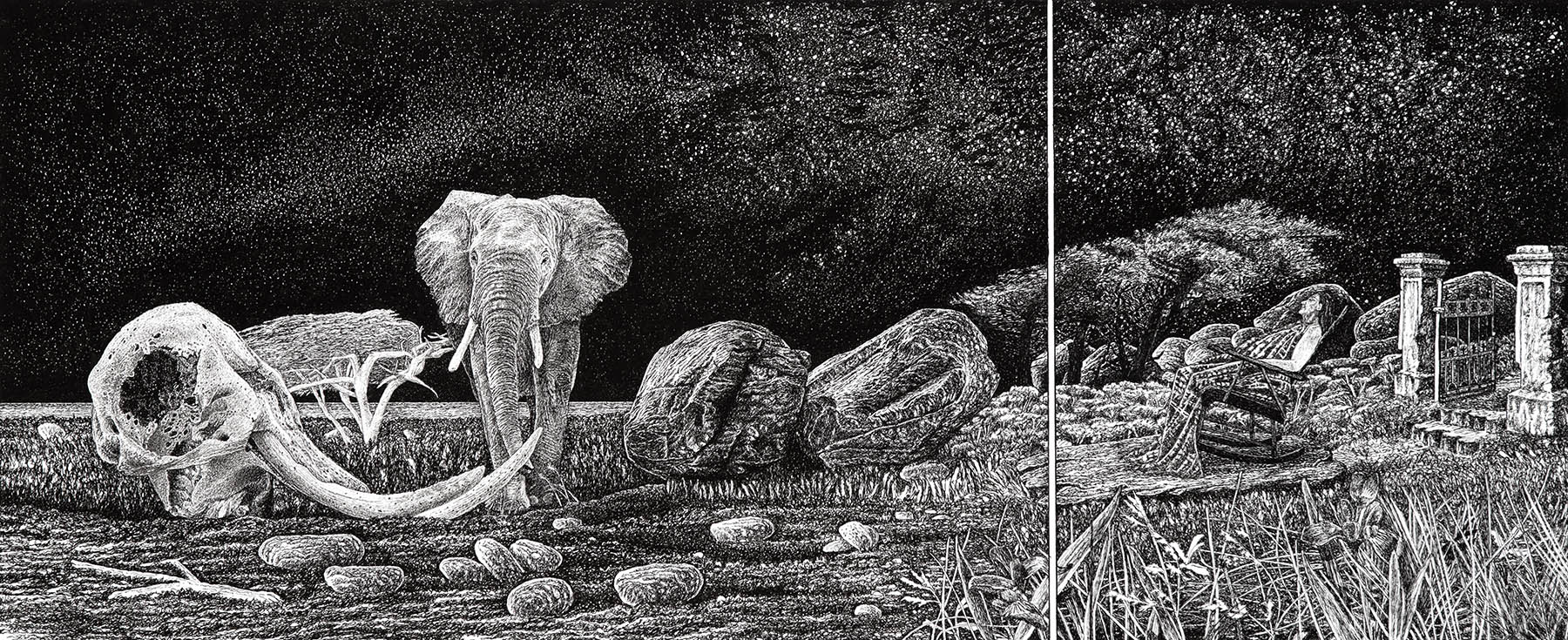

The Gifts Never Lost or Traded…, 2022

There are two more drawings in this exhibition that should be singled out. The first is “The Gifts Never Lost or Traded, those Dreams making vivid the Dialogue Between the Living and the Dead”. It is presented as a diptych, but one drawn on a single sheet of paper. The left panel (viewer’s left) is the larger. It shows an elephant approaching another elephant’s stripped and weathered skull. The skull still retains a magnificent pair of tusks. The right panel, half the width of the left one, shows an apparently sleeping woman in a rocking chair. She is covered by a knitted shawl. Her body is relaxed into the slackness of illness. Separating the two sides of the diptych is a narrow strip of unmarked paper. Rocks and vegetation rest and grow “under” this strip, so that the Labrador in which the woman passes her life extends into the Africa of the dead and living elephants. It is a picture about the continuities between sleeping and waking, between death and life, between organic and inorganic life forms, between past and present, between animals and humans, between time and eternity, between, as the title says, the living and the dead.

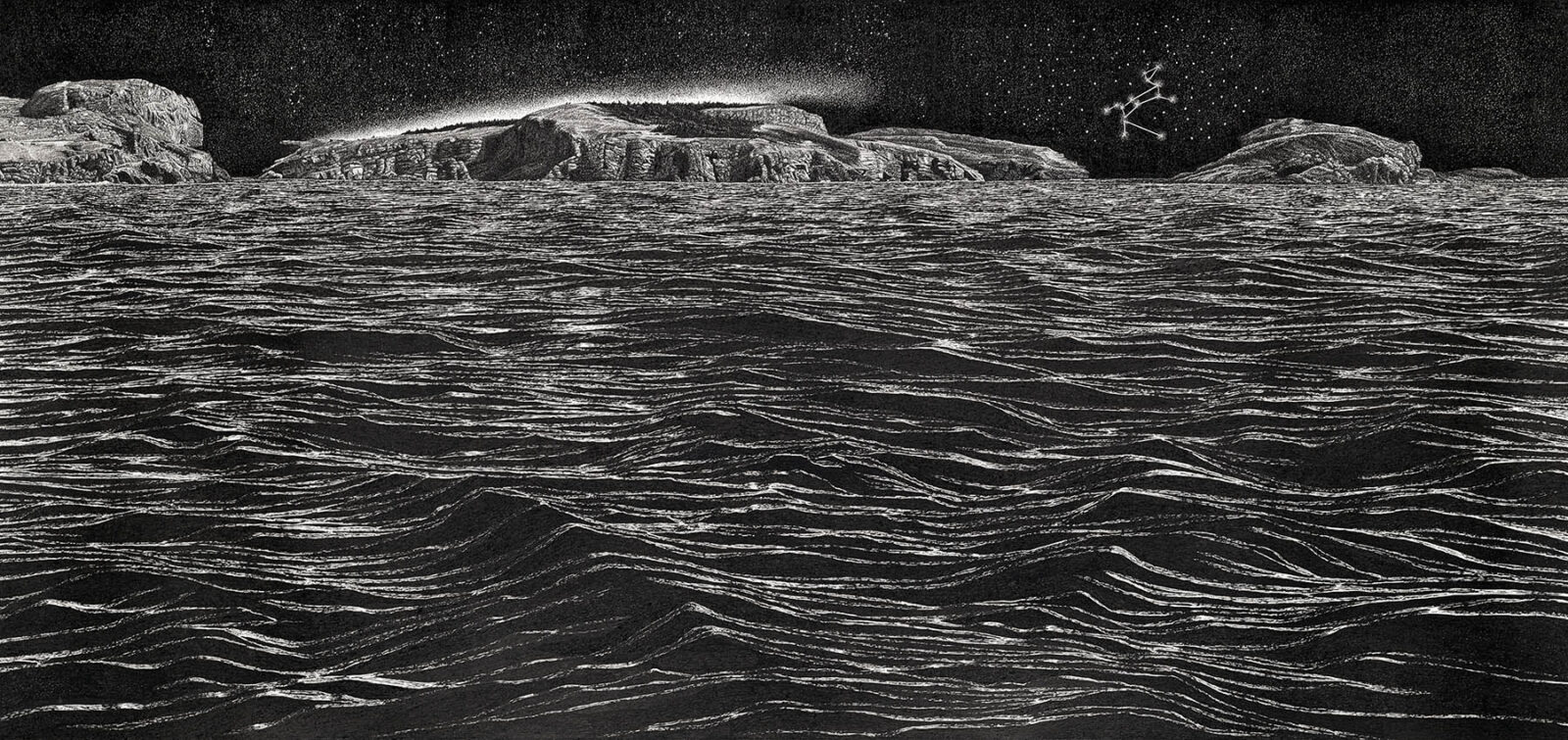

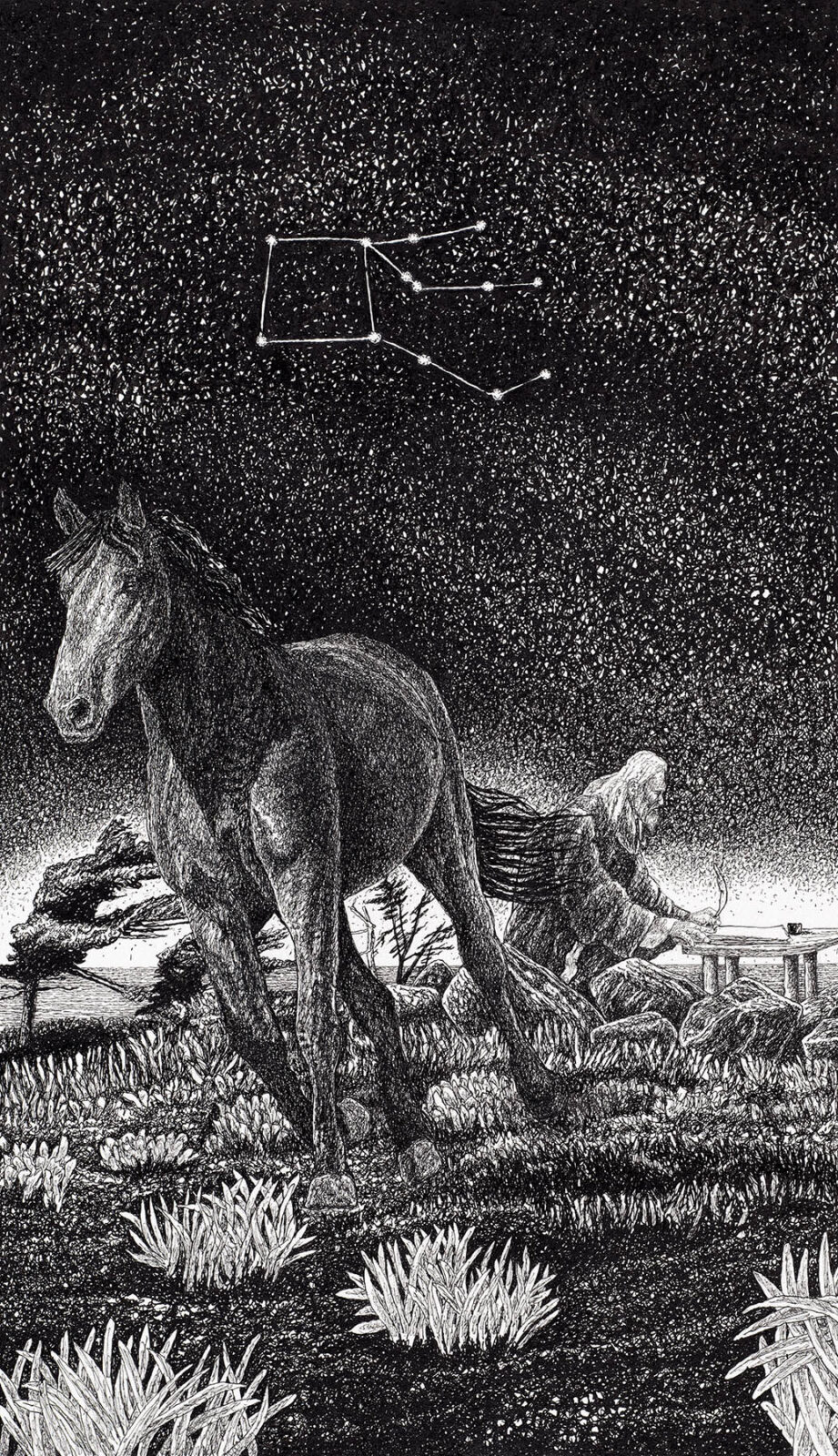

Raven and an Abandoned Percheron, Through Tidal Memory and Dream, 2024

The second drawing is entitled “Raven and an abandoned Percheron, through tidal memory and Dream”. The foreground is calm sea. The background is one of those star- filled skies only possible in the purest of atmosphere and the darkest of nights. The stars brim and spill with a quivering, liquid light. A fleet of four icebergs floats along the horizon. A large full moon hangs above them. Its head silhouetted by the moon, standing on a thick, flat floe, is a heavily built, unbridled work horse. Horse and floe are drifting out to sea. A raven flies beside them as if it were an attendant appointed.

In an exhibition containing many arresting images, this is one of the most transfixing. The horse can be going nowhere else but to its death. Yet its nobility and serenity place it beyond death. It enters the eternal life of its archetype. I remember the story Chubbs told me about his father in the boat speaking to his sons about catching fish and the necessary consent of many powers, entities, appetites.

I have asked Chubbs about the horse. He told me this story. (In Chubbs’ work there is always a story. It may be one’s own.) The horse appeared in L’Anse Au Clair in the summer of 1964 when Chubbs was nine. As the summer waned and grass withered, the horse had to forage further and further afield to find food. Possibly its owner had under- estimated how much more a large animal needed. Chubbs may well have been one of the last to see the animal alive. He happened to glimpse its owner leading it across the frozen bay to what is locally called the Reef, a rock formation on the eastern edge of the L’Anse Au Clair harbour. Chubbs saw the owner return across the ice alone. That is the end of the story. Cold pastoral. Art is another matter.

© April 2025

Peter Sanger

Poet and Essayist

Boyd Chubbs was born in L’anse Au Clair, on the southern coast of Labrador, in 1955. Chubbs came to Newfoundland in 1973 and it is in St. John’s that he consciously began his explorations in poetry, drawing and the guitar, the three passions which have sustained him. Chubbs states that there are no earliest memories of drawing or writing, only of the guitar which his late brother, Eric, gave him at the age of fourteen.

Chubbs studied in an art program at the College of Trades and Technology between 1973–1974 and from 1976–1980 he studied English, Sociology and Psychology at Memorial University.

In 1985 Boyd moved to Truro, Nova Scotia where he was poet in residence at Nova Scotia Teachers College from 1987–1990. He returned to Newfoundland in 1993 and in December of that year Christina Parker Gallery invited him to exhibit in the gallery year end exhibition.

Throughout the years of exhibiting with the gallery Boyd Chubbs has exhibited in eight solo exhibitions and over 20 gallery artist group exhibitions.